|

| May 28, 2019 | Volume 15 Issue 20 |

Designfax weekly eMagazine

Archives

Partners

Manufacturing Center

Product Spotlight

Modern Applications News

Metalworking Ideas For

Today's Job Shops

Tooling and Production

Strategies for large

metalworking plants

Industrial 3D printer prints directly from recycled shredded waste

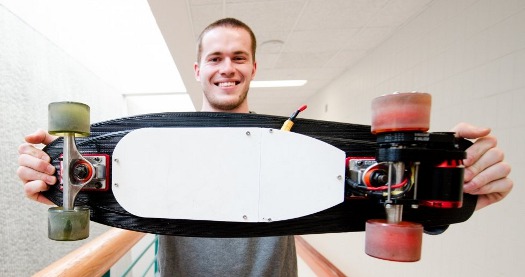

The Gigabot X machine can print large items like skateboard decks (shown here by Michigan Technological University researcher Aubrey Woern) directly from shredded, recylcable materials.

By Allison Mills, Michigan Technological University

Kayak paddles, snowshoes, skateboards. Outdoor sporting goods used to be a tough market for 3D printing to break into, but fused particle fabrication (FPF) can change that.

A team led by engineers from Michigan Technological University and re:3D, Inc. has developed and tested the Gigabot X, an open source industrial FPF 3D printer that can use waste plastic particles and reform it into large, strong prints. Because of the unique challenges presented by sporting goods -- size, durability, specificity -- the team chose several Upper Peninsula-inspired items.

In their new paper, published in Additive Manufacturing, the team lays out how fab labs, which are prototyping and technical workshops that allow personal digital fabrication, and other 3D-printing hubs like makerspaces, public libraries, or schools, can economically sustain themselves while printing environmentally friendly products using FPF. In some cases, the return on investment for a Gigabot X machine reached above 1,000 percent for high-capacity use paired with recyclable feedstock.

Aubrey Woern, a mechanical engineering student, leads the Open Source Hardware Student Enterprise Team and is co-founder of a company that turns recyclable plastic into 3D filament.

Recycle, print, repeat -- with Gigabot X

The Gigabot X is not the kind of 3D printer that fits on the kitchen table. Although these smaller printers also see a major return on investment for residential set-ups, the Michigan Tech Open Sustainability Technology (MOST) Lab saw a need beyond household prints.

"This isn't a gadget to make toys for your kids; this is an industrial machine meant to make real, large, high-performance products. With well over 1,000 fab labs worldwide spreading fast and morphing into environmentally friendly ‘green fab labs,' the Gigabot X could be a useful tool to add to their services as well as other makerspaces," said Joshua Pearce, Richard Witte Endowed Professor of Materials Science and Engineering and a professor in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering. "Of course, for our testing we wanted to use recycled plastic."

That's a hallmark of the Gigabot X. Last year, a Michigan Tech and re:3D collaborative study showed that the machine could be used with a wide range of plastics plucked from the waste stream to live on in a new productive life. The system is based on a previous design from the MOST Lab, the recyclebot, which makes waste plastic filament for 3D printers. Pearce's team has looked deep into better ways to sort, sift, and classify plastic to improve its 3D printability.

Recyclable feedstock takes plastic that otherwise would have been wasted and turns it into 3D-printed products.

Melting and extruding, however, does weaken plastic; it can withstand five cycles before it's mechanically compromised. What's new with the Gigabot X is a process called fused particle fabrication (FPF), or fused granular fabrication (FGF), that skips the step of making filament before 3D printing and saves one melt cycle. Basically, it prints directly from shredded waste. The Gigabot X's size and versatility to use any material including waste is reflected in the machine's economics.

Fab lab return on investment

While not cheap by household standards (the Gigabot X runs around $18,500), the upfront investment has greater potential return. The team used three case studies: a skateboard deck, double-bladed kayak paddle (both child-sized and adult-sized fitted on an aluminum pipe), and snowshoes.

Using their sporting goods prints, Pearce and his team compared costs of low-end and high-end options for commercially available products, prints with commercial filament, prints with commercial pellets, and prints with recycled plastic. They ran these against four capacity scenarios: continuous printing, one new start per day, two new starts per day, and printing once per week.

VIDEO: Money and tech viability of Gigabot X for FabLabs and small businesses.

The printed kayak paddle, which was the trickiest to produce and compare because of the metal pipe, was financially comparable to the least expensive off-the-shelf paddle. Skateboards and snowshoes were both easy to produce and significantly lower in cost than commercial products. FPF printing beat the economics of even the cheapest decks using commercial pellets and dropped in cost using waste plastic. Over their lifetime, if operated even only once a day, the Gigabot X could produce millions of dollars of sporting goods products.

"Once the capital costs are taken care of, which can often be less than a year, FPF or FGF machines have an enormous potential to make profit. Economically, they absolutely make sense," said Pearce. "The bottom line is that Gigabot Xs pay for themselves under a reasonable load and provide double or triple digit returns on investment under most scenarios. Essentially, if you're using it more than once a week, then you're making money, easily."

For green fab labs as well as the burgeoning makerspace scene around the world, the Gigabot X presents a customizable, open source, environmentally friendly, and fun option to help sustain its 3D-printing center.

[Editor's Note: MTU researchers did not comment on how to maintain consistency of the product.]

Published May 2019

Rate this article

View our terms of use and privacy policy