Synchronous Development: Learning to work together

Today, companies across numerous industries find themselves on the cusp of a product development revolution. The incorporation of software and electronics into mechanical-based products is driving a wave of new innovation as products become more like “intelligent systems” that are interactive, proactive, changeable, and upgradeable.

With software and electronics driving so much new product value, leading companies have begun to view and develop their products as “systems.” No longer do leaders develop the physical, mechanical product first and then merely force-fit the intelligence portions in at a later date. Instead, they take a systems-based approach that requires simultaneous and connected development to occur between software, electronics, and mechanical functions at the earliest design stages and to continue throughout the product development cycle.

This systems-based approach to designing products is drastically changing the product development landscape in the traditionally mechanical-based industries of automotive, aerospace and defense, and machinery. It is also profoundly affecting product development and innovation in the apparel, consumer products, and electronics industries. Consider just three recent examples of products that rely on the convergence of software, electronics, and mechanical:

Automotive drivetrains: Traditionally 100% mechanical, drivetrains are now almost 50% composed of electronics controlled by software to enable “drive-by-wire” maneuvering.

Mobile telephones: Convergence and a systems approach to new product development have led to the availability of mobile phones that play music, video, games, and more. Moreover, new innovations occur so rapidly that shelf life has diminished to less than six months in some cases.

Footwear: New athletic shoes are now equipped with microprocessors that automatically adjust the levels of support in the sole in order to match the terrain and runner’s activity level.

The functionality leaps apparent in these products are clear proof of the impact that a systems approach to product development has on innovation across industries. In addition, a systems approach enables companies to significantly increase product modularity. If designed with an optimal systems view, many products need only have their software and/or electronics modified to offer varying levels of functionality and performance.

Synchronizing your efforts

While embracing the wave of convergence between software, electronics, and hardware that drives innovation and product modularity is crucial for winning in today’s market, many companies struggle to synchronize efforts in two areas critical to a systems-based approach to product design:

- Alignment of the design disciplines of electronics, software, and hardware throughout the new product development cycle;

- Alignment of the product management, design, and manufacturing teams needed to ensure that core products can be manufactured as intended.

To overcome these challenges, industry leaders are adopting a strategy of Synchronous Product Development, or SPD, to guarantee the alignment of all product development stakeholders and the information they need to share. Those companies that best drive a SPD strategy will enjoy a sustainable competitive advantage for years to come by launching market-winning products faster and at lower costs than their competitors.

What is Synchronous Product Development?

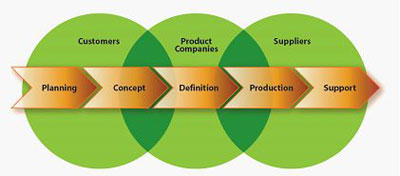

SPD is a set of business processes that coordinate and synchronize the activities and deliverables of global product development teams, working in multiple engineering disciplines, in any phase of the product lifecycle. SPD serves to bridge together the various design disciplines and, at the same time, ensure that designs reflect the needs of customers and the capabilities of the various manufacturing sites.

Figure 1. Synchronous Product Development

A major impediment to system development is ensuring that design activities are properly aligned with market requirements. This is even more complex when the product’s capabilities require early design collaboration between multiple design disciplines.

Efforts by one group are often compromised when they are confronted with limitations imposed upon their designs by the other engineering disciplines trying to fulfill competing product needs. In addition, product development teams must also cope with late-stage design changes caused by shifting customer needs and site-specific manufacturing capabilities.

Consider this scenario: A new interactive product that is being developed requires significant software modifications in order to meet new marketing requirements. The software modifications (enhancements) result in unacceptable response times, so a new processor is required to provide greater computational speed and capacity. But the new processor puts out more heat and thus requires changes be made to the product package to improve heat dissipation. Because identification of the need for a new processor and an upgraded package occur late in the design cycle, product launch has to be delayed.

Which design team made a mistake? Did they all make mistakes? Which team needs to re-work its product design and slip far behind schedule on this project and perhaps on other projects as well? And who will be responsible for the extra costs incurred for re-developing a solution?

Situations like this often give rise to software, electronics, and mechanical design teams viewing and treating one another as adversaries rather than as teammates working together toward a common goal.

Figure 2. New car product development lifecycle without SPD.

Many companies have disjointed processes in place for keeping design teams abreast of shifting product requirements and manufacturing-based design parameters — and navigating these processes makes it even tougher for designers to do their jobs. Design teams must focus on design, not on tracking down requirements.

This is where SPD pays off. With a SPD strategy in place, designers work from a single source of product information that is continuously updated in real time by all involved parties. Changes can be automatically pushed to the various design and development teams as soon as they occur, furnishing teams with all of the information they require — and making sure they can focus on their core work.

Achieving SPD

SPD can be achieved when companies establish and adhere to the three crucial components of product development: (1) a product planning framework, (2) unified product design, and (3) an aligned view for both designers and manufacturers.

A product planning framework: Often referred to as “system design,” a product planning framework is a top-down approach to sorting products into planned options and features across all design disciplines, ensuring a consistent and interoperable development process.

Most companies’ software, electronics, and mechanical design disciplines utilize independent design logic and processes — but a systems-based design process provides one unified set of processes and logic to ensure that all design disciplines are operating in unison.

A product planning framework enables and mandates that all design disciplines take the following critical steps when designing component parts to ensure a systems approach:

- Capture market/customer requirements

- Plan product options and features to account for multiple design disciplines

- Track design iterations

- Validate that requirements have been satisfied

- Design for part re-use and modularity

This type of product planning has proven successful in software development and aerospace and defense product development environments — both of which have a highly specialized need to continuously capture and validate data. Today, as companies in all industries need to develop increasingly complex products to meet shorter market opportunities, they too must establish a product planning framework — prior to defining their products.

Figure 3. New car product development lifecycle with SPD.

Unified product design: With a solid understanding of a product’s requirements in place, development teams can begin to design the product itself. This design occurs in two stages: informal and formal.

Informal product design occurs when designers have the ability to “white board” their ideas and collaborate on them in an environment that is unencumbered by design rules. Informal product design should also enable designers to view and mark up one another’s work within any design tool and across multiple design tools. Such a free-flowing environment enables designers to be as creative as possible, enabling true innovation to take place.

Formal product design then brings order to the creative environment. In this stage, rules are applied to design processes to ensure that all of a product’s component parts are accounted for and seen by all stakeholders in a unified environment. The rules mandate that teams take the following steps:

- Consolidate part design content into a single definition of the engineering BOM

- Adhere to one cross-functional engineering change process

- Qualify and manage purchased parts

Taking these steps, designers are able to follow a path to product development success that is predictable, consistent, and repeatable.

An aligned view for both designers and manufacturers: Many product companies have adopted a “design anywhere, build anywhere” strategy, spreading their manufacturing sites across the globe. One of the lesser known problems with a global manufacturing strategy is that not all plants can work from the same Manufacturing BOM because of variables such as local supplier constraints, manufacturing capabilities, and/or local market requirements and regulations.

To ensure that each site manufactures products to specification, manufacturing and design teams must be able to collaborate and detect and correct problems before specs are released to manufacturing. Aligning design and manufacturing views of the product can be achieved by bringing Manufacturing BOM management into the formal product definition stage within engineering, thereby allowing design and manufacturing teams to apply all the rules and processes of the formal product definition environment to the Manufacturing BOM. This results in a streamlined product launch — and fewer costly product recalls.

A staged approach

Many companies already leverage elements of SPD and should not look to throw away processes that already prove effective for launching new products. Doing so would disrupt design teams and interfere with ongoing competitive practices.

However, bringing planning and order to existing product development activities will provide greater levels of speed and consistency in driving new products to market. Companies should instead look to improve their current activities by identifying areas for improvement and applying SPD best practices to them in a staged approach.

This approach provides several key benefits:

- Product development teams can continue to work in an environment that is comfortable and well-known to them

- ROI of SPD investments can be proven at each stage of implementation prior to investment in subsequent stages

- Companies can target the areas of greatest need first to gain competitive advantage and then obtain executive commitment for future stages

Holistic, not task-specific

To successfully implement a SPD strategy, companies need to look at product development holistically, rather than from the standpoint of a single development tool. Task-specific products have increased the use of disparate tools to the detriment of synchronous product development efforts. When product development teams focus on tools, they lose sight of the overall product planning framework needed to align the entire organization’s product development efforts.

Taking a narrow, tool-driven approach to product development can have dire consequences, including:

Over-reliance on innovative designs: Design innovation, while important, is only one element of successful new product development. Companies that consistently win do so by excelling in multiple areas of product development, such as:

- Understanding customer needs

- Reaching market faster than competitors

- Minimizing product scrap and re-work

- Designing for manufacture

- Streamlining supplier collaboration

- Embracing only those design tools that correspond to true design needs

Tool-encumbered product development: If the design tools are the only source of product development activities, then companies’ product development efforts can only progress as quickly as their design tools do.

Extreme competitive disadvantage: While competitors synchronize product development efforts and streamline time-to-market through SPD, tool-dependent companies miss market opportunities and eventually become irrelevant.

Conclusion

By leveraging SPD, companies minimize risks while creating an environment for streamlined information sharing. This forms the core for lean manufacturing and modular product development — allowing them to develop and deliver new innovations and follow-on products to market faster than the competition.

By hitting existing and new markets fast with a variety of new product choices, companies can virtually “lock out” competitors’ offerings or force competitors to forego any attempt to enter newly formed markets.

The bottom line is that a strong SPD strategy can put your company miles ahead of the competition and result in increased margins for a longer period of time.

About the authors

Jonathan Gable has over 16 years in the product lifecycle management (PLM) software industry. He currently serves as ENOVIA MatrixOne’s vice president, product management. In this role, he is responsible for defining how ENOVIA MatrixOne’s PLM applications solve the most challenging product development challenges. Gable joined the company from Sherpa Corporation, where he was an application engineer. Previous to Sherpa, Gable was with EDS, where he was a systems engineer. He holds a Bachelor of Science degree in Industrial Engineering from Lehigh University and a Master of Science degree in Engineering Management from the University of Michigan.

Andrew DeTolla has over 25 years of experience in product lifecycle management (PLM), computer aided design, manufacturing, and engineering (CAD/CAM/CAE) software industries. He currently serves as ENOVIA MatrixOne’s director, product management where he is responsible for defining the capabilities of engineering and manufacturing horizontal PLM applications.

Want more information? Click below.

ENOVIA MatrixOne

© Nelson Publishing, Inc. All Rights Reserved