|

| July 16, 2024 | Volume 20 Issue 27 |

Designfax weekly eMagazine

Archives

Partners

Manufacturing Center

Product Spotlight

Modern Applications News

Metalworking Ideas For

Today's Job Shops

Tooling and Production

Strategies for large

metalworking plants

55 Years Ago: Apollo 11 launch and Moon landing - Part 1

The huge, 363-foot-tall Saturn V rocket with the Apollo 11 space vehicle launched at 9:32 a.m. EDT on July 16, 1969, from Pad A, Launch Complex 39 at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida. This view of liftoff was taken by a camera mounted on the mobile launch tower. [Credits: NASA]

By John Uri, NASA Johnson Space Center

An estimated 1 million people gathered on the beaches of central Florida to witness first-hand the launch of Apollo 11, while more than 500 million people around the world watched the event live on television.

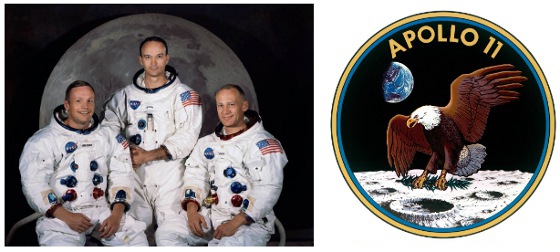

Officially named as a crew just six months earlier, Commander Neil A. Armstrong, Lunar Module Pilot (LMP) Edwin E. "Buzz" Aldrin, and Command Module Pilot (CMP) Michael Collins were prepared to undertake the historic mission. Previous Apollo crews had tested the spacecraft in Earth orbit and around the Moon, and only two months earlier, Apollo 10 had completed a dress rehearsal to sort out all the unknowns for the lunar landing. Now it was time to attempt the landing itself.

Left: Apollo 11 crew of (left to right) Armstrong, Collins, and Aldrin. Right: Apollo 11 crew patch.

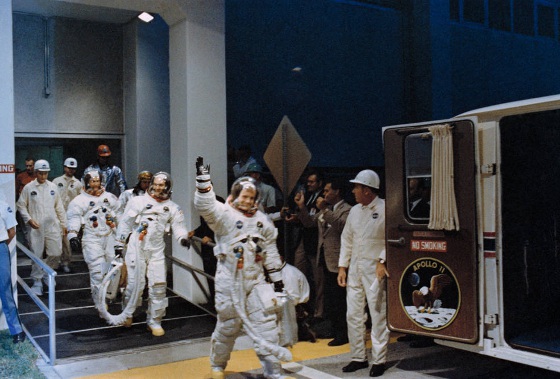

The astronauts' day on July 16, 1969, began with a 4 AM wake-up call from Chief of the Astronaut Office Donald K. "Deke" Slayton. After the traditional pre-launch breakfast with Slayton and back-up CMP William A. Anders, the crewmembers donned their spacesuits and took the Astrovan to Kennedy Space Center's (KSC) Launch Pad 39A. Workers in the White Room assisted them into their seats in the Command Module (CM) Columbia, Armstrong into the left-hand couch, Collins into the right, and finally Aldrin into the middle. After the pad workers closed the hatch to the capsule, the astronauts settled in for the final two hours of the trouble-free countdown. As Armstrong noted just before liftoff, "It's been a real smooth countdown."

Pre-launch breakfast in crew quarters (left to right) Anders, Armstrong, Collins, Aldrin, and Slayton.

Apollo 11 astronauts (left to right) Aldrin, Collins, and Armstrong leaving crew quarters to enter the Astrovan for the ride to Launch Pad 39A.

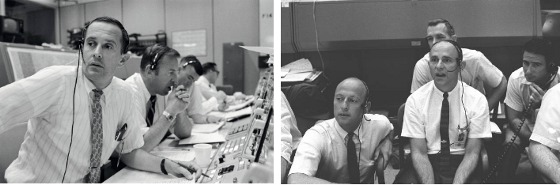

At precisely 9:32 AM EDT, Apollo 11 lifted off from Launch Pad 39A to begin humanity's first attempt at a manned lunar landing. Engineers in KSC's Firing Room 1 who had managed the countdown handed over control of the flight to the Mission Control Center (MCC) at the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC), now the Johnson Space Center in Houston, as soon as the rocket cleared the launch tower. In MCC, the Green Team led by Flight Director Clifford E. Charlesworth took over control of the mission. The Capcom, or capsule communicator, the astronaut in MCC who spoke directly with the crew during launch, was Bruce McCandless.

The three stages of the Saturn V performed flawlessly and successfully placed Apollo 11 into low Earth orbit. For the next two-and-a-half hours, as the Apollo spacecraft still attached to its S-IVB third stage orbited the Earth, the astronauts and MCC verified that all systems were functioning properly. McCandless then called up to the crew, "Apollo 11, you're go for TLI," the Trans Lunar Injection, the second burn of the third-stage engine to send them on their way to the Moon.

Liftoff of Apollo 11.

Left: Flight Director Charlesworth in MCC during Apollo 11 launch. Right: Engineers in KSC's Firing Room watch the launch after Apollo 11 cleared the launch tower.

Left: A ring of condensation forms around the Saturn V rocket as it compresses the air around it during the launch of Apollo 11, framed with an American flag in the foreground. Middle: A view of a low-pressure system taken during Apollo 11's first orbit around the Earth. Right: Collins inside the CM during its first orbit around the Earth.

Two hours and 44 minutes after liftoff, the third-stage engine ignited for the six-minute TLI burn, increasing the spacecraft's velocity to more than 24,000 miles per hour, enough to escape Earth's gravity. Armstrong called down to the ground after the burn, "That Saturn gave us a magnificent ride. It was beautiful."

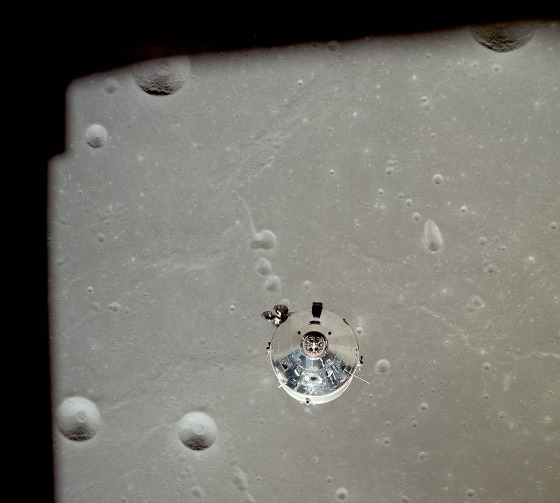

A little over three hours after launch, and already more than 3,000 miles from Earth, the Command and Service Module (CSM) separated from the spent third stage to begin the transposition and docking maneuver. Collins flew the CSM Columbia out to a distance of about 100 feet and turned it around to face the now exposed LM Eagle still tucked into the top of the third stage. He slowly guided Columbia to a docking with Eagle, then extracted it from the third stage which was sent on a path past the Moon and into orbit around the Sun. During the maneuver, the spacecraft had traveled another 3,000 miles away from Earth.

The LM Eagle still in the third stage during the transposition and docking maneuver, as seen from the CM Columbia.

Aldrin inside the LM Eagle during the first activation, on the way to the Moon.

During the rest of their first day in space, MCC informed the crew that because the launch and TLI had been so precise, the planned first midcourse correction would not be needed. The astronauts were finally able to remove the spacesuits they'd been wearing since before launch.

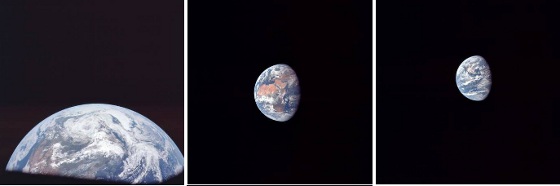

Armstrong called down with birthday wishes for the state of California (200 years old) and for Dr. George E. Mueller, NASA Associate Administrator for Manned Space Flight (stated as "not that old"). In MCC, Flight Director Eugene F. Kranz's White Team of controllers took over, with astronaut Charles M. Duke as the new Capcom. The astronauts provided a pleasant surprise with an unscheduled 16-minute color television broadcast, treating viewers on Earth with spectacular scenes of their home planet. They then placed their spacecraft in the Passive Thermal Control (PTC) or barbecue mode, rotating at three revolutions per hour, to evenly distribute temperature extremes. Finally, about 13 hours after launch and a very long day, the crew began its first sleep period, with Apollo 11 about 63,000 miles from Earth.

Overnight, Flight Director Glynn S. Lunney's Black Team of controllers, with astronaut Ronald E. Evans as Capcom, watched over the spacecraft's systems. By the time the astronauts awoke, now almost 110,000 miles from Earth, Charlesworth's Green Team was back on console. Capcom McCandless provided a morning news update to the crew, including a status of the Soviet Luna 15 robotic spacecraft that had launched three days before Apollo 11 and was still on its way to the Moon.

The crew conducted the only midcourse correction needed during the coast to the Moon, a three-second burn of the Service Propulsion System (SPS) engine to lower the closest point to the Moon from 200 miles to 69 miles. McCandless informed the astronauts that Luna 15 had entered an elliptical orbit around the Moon, but that its objectives were still not clear.

Photographs taken from Apollo 11 show the receding Earth (left to right) shortly after the transposition and docking maneuver, from 113,000 miles, and from 144,300 miles.

The crew conducted a scheduled TV broadcast from about 150,000 miles, showing views of a much smaller Earth with Armstrong providing a detailed description of the planet. He then turned the camera inside the cabin for views of the astronauts and showing viewers their food pantry, concluding with filming the Apollo 11 mission patch on their flight suits. The broadcast lasted 35 minutes. The crew soon after settled down for its second night's sleep in space, which MCC extended since another midcourse correction the next morning was not needed as their trajectory remained very precise.

In Houston, astronaut Frank Borman and Christopher C. Kraft, Director of Flight Crew Operations, held a press conference about Luna 15. NASA managers were concerned that with Luna 15 now in orbit around the Moon and its objectives still not clear, it might interfere in some way with Apollo 11. Borman had visited Moscow earlier in July and met with Academician Mstislav V. Keldysh, President of the Soviet Academy of Sciences. Taking advantage of this new acquaintance, Borman telephoned Keldysh and expressed NASA's concerns. Keldysh assured Borman that Luna 15 would not interfere with Apollo 11, and in an unprecedented action in American-Soviet space relations he telegraphed Luna 15's precise orbital parameters to Borman. The Soviets didn't divulge Luna 15's true intentions, stating only that it would stay in lunar orbit for two days.

The major activity for Apollo 11's third day in space was the first activation and inspection of the LM Eagle, which the crew televised to the ground from about 201,000 miles away. Armstrong described the status of the docking mechanism, "Mike must have done a smooth job in that docking. There isn't a dent or a mark on the probe" -- a compliment of Collins' excellent piloting skills. When they opened the hatch to Eagle, the lights came on automatically, prompting Capcom Duke to say, "How about that. Just like the refrigerator."

Aldrin floated into the LM, taking the TV camera with him, and provided viewers with an excellent tour of all of its systems, as well as the astronauts' spacesuit helmet visors and backpacks. The broadcast lasted one hour and 36 minutes, after which Aldrin and Armstrong returned to Columbia and closed the hatches. Soon after, Apollo 11 passed into the Moon's gravitational sphere of influence, 214,086 miles from Earth and 38,929 miles from the Moon. The crew settled down for its third sleep period of the flight.

While the crew slept, MCC decided that a planned midcourse correction that day would also not be required, and they extended the crew's rest. Shortly after they woke for their fourth day in space, Apollo 11 crossed into the Moon's shadow and they could observe the solar corona. They could see the Moon's surface lit by Earthshine, and for the first time they could see stars and constellations clearly.

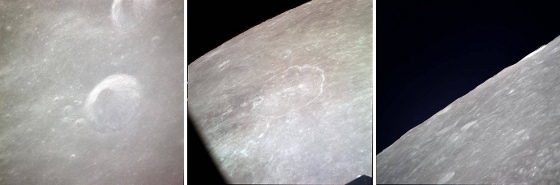

Capcom astronaut and back-up Apollo 11 LMP Fred W. Haise read up the morning news to the crew. An item of interest was that in its reporting of the mission, the Soviet newspaper Pravda called Armstrong the "Czar of The Ship." The Soviet press was indicating that Luna 15 would accomplish everything that all previous Luna spacecraft had done, the first public hint that it might be trying to return samples from the Moon. Armstrong provided the following description of the Moon, which the astronauts were seeing for the first time:

"The view of the Moon that we've been having recently is really spectacular. It fills about three-quarters of the hatch window, and of course, we can see the entire circumference, even though part of it is in complete shadow and part of it's in Earthshine. It's a view worth the price of the trip."

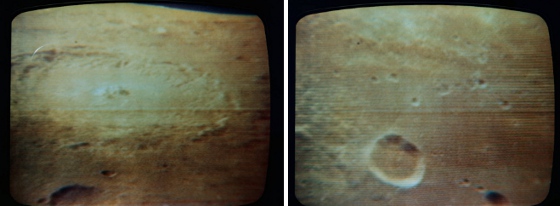

Three views of the lunar far side. Left: Crater Glazenap. Middle: Crater King. Right: Looking toward the Moon's limb over the rim of Crater Mendeleev.

Shortly after, as Apollo 8 and 10 had done before, Apollo 11 sailed behind the Moon and all contact with Earth was cut off. Eight minutes later, they fired the SPS engine for the six-minute Lunar Orbit Insertion-1 (LOI-1) burn, and Apollo 11 entered into an elliptical lunar orbit.

As Apollo 11 came around from the back side of the Moon, the crewmembers saw their first Earthrise and Aldrin reported their status to MCC, "The LOI-1 burn just nominal as all getout, and everything's looking good." A few minutes later, the astronauts got their first view of the approach to their landing site in the Sea of Tranquility, which was still in darkness. By the time of the landing the next day, the Sun would have risen at the landing site, the low angle illumination providing optimal lighting for the landing. Of the approach Armstrong commented, "It looks very much like the pictures, but like the difference between watching a real football game and one on TV. There's no substitute for actually being here."

Two views of the Moon from Apollo 11's first TV broadcast from lunar orbit. Left: The Crater Langrenus. Right: The Mare Fecunditatis.

During their second lunar orbit, the crew televised views of the Moon across much of the near side. At the end of that revolution, and once again behind the Moon, they fired the SPS engine for the 17-second LOI-2 burn to circularize their orbit. Armstrong and Aldrin entered the LM Eagle for the second time to begin activation and transfer of equipment such as cameras. Aldrin reported that he could see the entire landing area as they flew over it. They returned to Columbia, and the entire crew settled down for its first sleep period in lunar orbit. It was also their final night before attempting the first Moon landing the next day.

MEN LAND ON THE MOON!!

Words such as these were emblazoned in dozens of languages on the front page of newspapers around the world, echoing the first part of President John F. Kennedy's bold challenge to the nation, made more than eight years earlier: to land a man on the Moon. That part was successfully accomplished on July 20, 1969. The second part of the challenge, the safe return to Earth, would have to wait four more days.

Apollo 11 astronauts Neil A. Armstrong, Edwin E. "Buzz" Aldrin, and Michael Collins awoke to start their fifth day in space at the end of their ninth revolution around the Moon. In Mission Control at the Manned Spacecraft Center, Eugene F. Kranz's White Team of controllers arrived on console, with astronaut Charles M. Duke serving as Capcom. After a quick breakfast, Aldrin and Armstrong began re-activating the Lunar Module (LM) Eagle, including deploying its landing gear, and donned their pressure suits. Near the end of the 12th orbit around the Moon, Duke radioed up to Apollo 11 that they were GO to undock.

The event took place behind the Moon during the start of their 13th revolution, with the astronauts filming each other's spacecraft as they began their independent flights. After they reappeared from behind the Moon, Armstrong radioed their status to MCC saying, "The Eagle has wings." Collins in the Command Module (CM) Columbia observed, "I think you've got a fine-looking flying machine there, Eagle, despite the fact you're upside down," prompting Armstrong to reply, "Somebody's upside down."

Eagle shortly after undocking.

Columbia shortly after undocking.

From this point on, it was time to get down to business as events happened rather quickly. As the Moon landing attempt was less than an hour away, the viewing gallery in Mission Control was filling with NASA managers from across the agency, and many astronauts were present in the control room itself to witness the historic event. Later during the 13th orbit, about 10 minutes before Apollo 11 disappeared again behind the Moon, Duke radioed up the GO for Descent Orbit Insertion (DOI).

The DOI burn, a 30-second firing of the LM's Descent Propulsion System (DPS) engine, took place behind the Moon, lowering the low point of Eagle's orbit to about 50,000 feet, as close as Apollo 10 got to the Moon's surface. The two craft now flying separately reappeared from behind the Moon on their 14th orbit. Duke radioed up the GO for Powered Descent Initiation (PDI), the beginning of the landing maneuver. Eagle's antenna repeatedly lost lock on the Earth, so Mission Control had to communicate with Eagle through Collins in Columbia until reliable radio links were re-established.

At the beginning of PDI, the LM's DPS engine ran at 10% thrust for 26 seconds for a smooth initial deceleration before increasing to full thrust. Eagle was flying engine first and windows facing down toward the Moon's surface and was about 300 miles east of the landing site in the Sea of Tranquility. Eagle's attitude allowed Armstrong to track landmarks as they passed over them against the predicted times.

Based on Eagle passing landmarks about two to three seconds early, Armstrong predicted that they would land about three miles further downrange than planned -- and he was proved correct. At an altitude of 40,000 feet, Armstrong maneuvered Eagle to a windows-up orientation. This was in preparation for the pitch-over maneuver, which placed the windows facing forward in the direction of flight, and also positioned the landing radar so it could see the lunar surface.

At about 33,000-foot altitude, Armstrong and Aldrin were surprised by the first 1202 program alarm, which they had not seen in simulations. After a few seconds of analysis in MCC, Duke gave them a GO to proceed. The alarm simply meant the computer was overloaded with too much data and couldn't process it all, but controllers felt confident they could proceed with the landing. When a second 1202 alarm sounded less than a minute later, Duke once again gave the GO to proceed.

Eagle maneuvered to a more vertical orientation for the final phase of the descent. At about 5,000 feet and descending about 100 feet per second, Armstrong took over manual control of Eagle's attitude. As they passed through 3,000 feet with their descent rate slowed to 70 feet/second, Duke gave them the GO for landing, and they received the 1201 program alarm. Once again, Duke gave them the GO to proceed. Another 1202 flashed at about 1,000 feet altitude. At about 600 feet, noticing Eagle's computer was taking them down into a boulder-strewn area near West Crater, Armstrong took over manual control of the descent. He pitched Eagle to a more vertical orientation, which slowed the descent, and decided to overfly the rough area and look for smoother terrain to land on.

Armstrong found and flew to a clearer spot for landing, and Aldrin called out that he saw the LM's shadow on the Moon. Armstrong picked his final spot, about 60 meters east of Little West Crater. At about 100 feet, the fuel-quantity warning light came on, indicating only 5% fuel remaining, giving Armstrong about 90 seconds of hover time left. With 60 seconds of fuel remaining, they were down to about 40 feet and the descent engine was kicking up dust from the surface, increasingly obscuring Armstrong's visibility.

At precisely 3:17:40 PM Houston time on July 20, 1969, Aldrin called out "Contact light," indicating that at least one of the three 67-inch probes hanging from the bottom of three of the LM's footpads had made contact with the Moon. Eagle drifted to the left when three seconds later, Armstrong called out, "Shutdown," followed by Aldrin's, "Okay. Engine stop," indicating the DPS engine was shut off.

They were on the Moon.

VIDEO: Moon landing. [Credits: National Archives]

In Houston, Duke noted via telemetry that the engine had shut down, and called to Armstrong and Aldrin, "We copy you down, Eagle." Armstrong responded with the historic words, "Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed."

Left: In Mission Control during the descent to the Moon (left to right) Capcom Duke, and Apollo 11 crewmembers James A. Lovell and Fred W. Haise. Right: In Mission Control during the Moon landing (left to right) Apollo 12 prime crewmembers Charles Conrad and Alan L. Bean and their backups David R. Scott and James B. Irwin.

Next week Part 2: Stepping out in a new frontier and going home.

Learn more about NASA history at nasa.gov/history/.

A big thanks to NASA and author John Uri for penning such interesting and detailed accounts for all of us to enjoy.

Published July 2024

Rate this article

View our terms of use and privacy policy